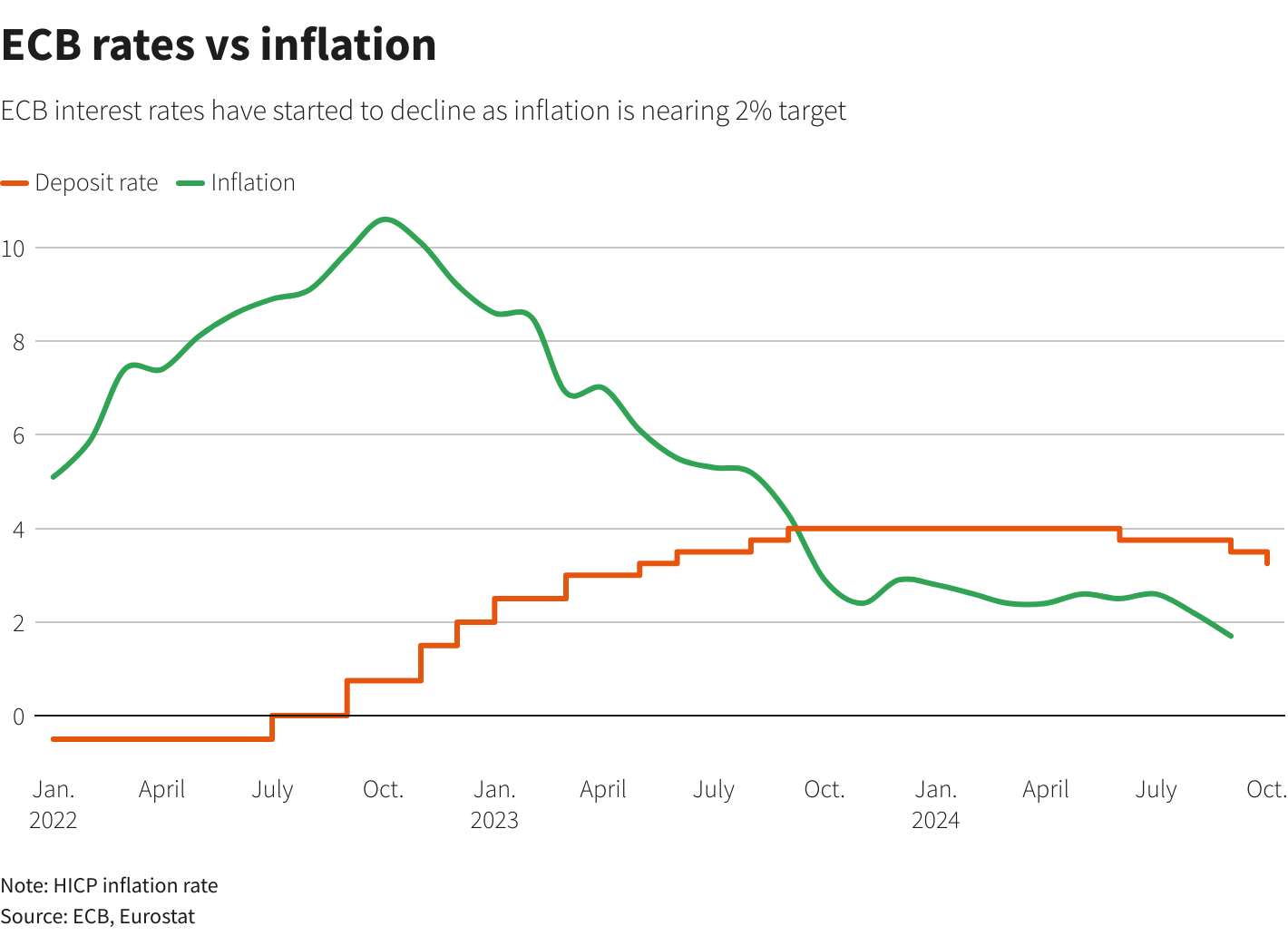

Oct 17 (Reuters) – The European Central Bank cut interest rates on Thursday for the third time this year, saying inflation in the euro zone was increasingly under control while the outlook for the bloc’s economy was worsening.

The first back-to-back rate cut in 13 years marks a shift in focus for the euro zone’s central bank from bringing down inflation to protecting economic growth, which has lagged far behind that of the United States for two years straight.

“We believe the disinflationary process is well on track and all the information we received in the last five weeks were heading in the same direction – lower,” ECB President Christine Lagarde told a press conference.

Lagarde did not provide hints about future moves but four sources close to the matter told Reuters a fourth cut in December is likely unless economic or inflation data turns around in the coming weeks.

Yet the U.S. elections, and the threat of fresh trade tariffs if Donald Trump is elected president, were seen as a major source of uncertainty, the sources said.

Asked about that risk, Lagarde said any trade obstacles were a “downside” for Europe.

“Any restriction, any uncertainty, any obstacles to trade matter for an economy like the European economy, which is very open,” she said, adding that the ECB was also “very attentive” to possible oil price moves linked to the Middle East conflict.

However, she added that the ECB did not expect recession at present and was still working on the assumption that the economy would stage a “soft landing”, jargon for lower – but still positive – growth.

The quarter-point cut brings the rate that the ECB pays on banks’ deposits down to 3.25%. Money markets are almost fully pricing in three further reductions through next March.

“We believe that downside risks to growth in a context of easing inflationary pressure will lead to more rate cuts starting in December and continuing in 2025 until interest rates are back around a neutral level, that the ECB itself estimates around 2%,” Gianluigi Mandruzzato, a senior economist at EFG Asset Management, said.

INFLATION AND GROWTH

The ECB can finally claim it has all but tamed the worst bout of inflation in at least a generation.

The ECB noted pay hikes are still supporting “domestic inflation” – that is growth in the price of services and goods that don’t rely much on imports – but this too was waning.

“Domestic inflation remains high, as wages are still rising at an elevated pace,” it said. “At the same time, labour cost pressures are set to continue easing gradually, with profits partially buffering their impact on inflation.”

Yet the economy has had to pay a high price for that.

A resilient labour market is also now starting to show some cracks, with the vacancy rate – or the proportion of vacant jobs as a share of the total – falling from record highs.

“The ECB has been overly cautious in the past and it is good news that Lagarde does not make the same mistake twice,” said Markus Ferber, a German member of the European parliament for the centre-right European People’s Party.

Yet some of the economic weakness is due to structural problems, such as the high energy costs and low competitiveness hobbling Europe’s industrial powerhouse Germany.

Lagarde repeated the ECB’s customary call on Europe’s politicians to push ahead with “ambitious” reforms to make the region’s economy more productive, competitive and resilient.

Sign up here.

Editing by Hugh Lawson; Editing by Sharon Singleton

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.