There are, broadly speaking, two competing theories that help to explain why Argentina has a long history of financial turmoil.

One emphasizes Argentina’s tradition of patronage politics, its complex system of fiscal federalism (and the difficulty reigning in powerful provincial governors) and the resulting difficulties Argentina has faced in maintaining fiscal discipline.

More on:

Argentina’s chainsaw-wielding libertarian President has—it would seem—solved this problem. The formal budget is in balance, and the true deficit, including the “hidden” deficit at the central bank, has been substantially reduced.

The other emphasizes the difficulty Argentina has faced generating foreign exchange—and risks created by Argentina’s low level of foreign exchange reserves relative to Argentina’s substantial import needs and its relatively large stock of external debt.

Argentina needs foreign exchange reserves in part because it lacks a strong export base. Goods exports tend to vary between $60 billion and $90 billion a year.* The services account is in chronic deficit. That isn’t a large sum of exports relative to the government’s $200 billion in external debt (including the external debt of Argentina’s central bank) and the economy’s nearly $300 billion in external debt. In fact, Argentina would be in substantially more trouble if it was paying a market rate on its external debt, which is now mostly low coupon bonds from the 2020 restructuring and official loans.

From this perspective, Argentina’s recent need for a lifeline from the U.S. isn’t much of a surprise. President Milei inherited a depleted Central Bank as well as a swollen budget.

He initially allowed a necessary depreciation and crushed imports to rebuild reserves while ruthlessly cutting public spending, including through draconian cuts to public investment that aren’t sustainable in the long run.

More on:

President Milei then shifted to a strong peso policy to help bring inflation down. The peso was allowed to slowly depreciate (crawl) vs. the dollar, but at a slower pace than inflation. The price-adjusted (real) value of the peso soared, as did imports.

Keeping the peso strong took priority over rebuilding foreign exchange reserves. The crawling peg was replaced with a band when Argentina received a new $12 billion loan from the IMF in April.

That cash infusion was largely used to offset foreign currency debt payments. Planned purchases of foreign exchange in the market deferred to support ongoing peso strength. Argentina thus missed the reserve target in its IMF program (net reserves were close to negative 5 billion when the target was negative 1 billion; the IMF nets out the PBOC swap and the domestic foreign exchange deposits of the banks and the deposit insurance fund). Argentina had to get a waiver of its net reserves target to receive the second tranche of IMF funds in the late summer. That was a very clear signal, as the reserves target was presented in April as the anchor of the IMF’s support.

It is worth diving a bit more deeply into Argentina’s reserves. The central bank reports holding about $40 billion in total reserves—a sum inflated by the $14 billion Argentina received from the IMF this year, and the $40 billion that President Macri borrowed back in 2018 and 2019. But even setting aside the fact that Argentina’s foreign exchange reserves are far smaller than the $54 billion that Argentina has borrowed from the IMF over the years, the reported total is misleading.

Net out the $7 billion in gold (usable in an emergency, but not for standard exchange rate management) and holdings of foreign exchange are around $33 billion. But $13 billion or so of that is held in Chinese yuan and can only be used with the permission of China’s central bank—which isn’t likely to be granted to a regional ally of the United States. Of the remaining $20 billion, over $12 billion is foreign exchange that the domestic banking system has put on deposit at the central bank, and another $2 billion is from Argentina’s deposit insurance funds. Those reserves cannot be used without putting the stability of the banks at risk. That leaves very modest levels of truly usable reserves, at well under $10 billion.

The IMF program’s definition of net reserves sets aside the recent funds borrowed from the IMF, the swap from China, the $12 billion that the government owes the domestic banks, and the roughly $2 billion in foreign exchange Argentina’s deposit insurance fund. The result is a negative number; see the following table from IMF’s April 2025 staff report.

There are other additional foreign currency-linked liabilities. For example, the central bank has sold $9 billion in peso-settled contracts that provide insurance against changes in the peso dollar exchange rate.*

Argentina simply isn’t operating with a healthy level of foreign reserves by any measure.

That low level of reserves—and the fact that the government preferred a stronger peso to rebuilding reserves over the spring and summer—explains why Argentina had to rely on an estimated $2 billion in peso purchases from the U.S. Treasury to keep the peso inside its new band prior to the recent election.

Moreover, Argentina has been promised even more support from the Trump Administration, namely a $20 billion swap line that would allow the central bank to replenish its depleted stock of dollars after the election. ***

Argentina now faces a critical choice.

Many in Argentina believed that the pressure on the peso was largely a function of electoral uncertainty, and the possibility that the opposition would do well enough to reverse President Milei’s budget cuts. Holders of Argentine pesos didn’t want to hold pesos if there was a risk that the government would lose political support—and possibly access to the $20 billion swap from the U.S. Treasury. But that uncertainty is passed, and with a clear political course and a commitment to exchange rate stability, Argentine’s might bring their offshore dollars back home and generate a flow that supports the peso and allows Argentina to run a modest current account deficit. Iván Werning of MIT has persuasively laid out this argument.

Proponents of this view, which seem to include Treasury Secretary Bessent, note that the inflation-adjusted value of the peso has fallen by about 15 percent (on the BIS index) over the course of the year, and thus argue that the peso can be sustained inside the new band with a modest amount of additional support from the U.S. (and perhaps the IMF in the future).

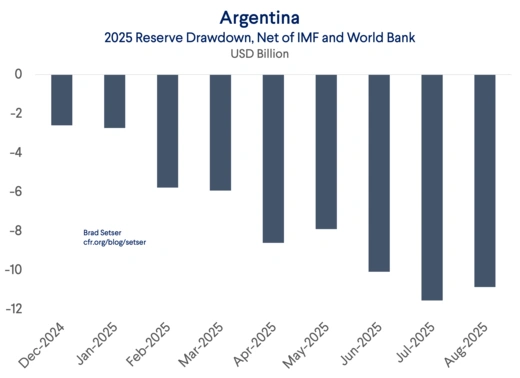

But that approach has substantial risks. Argentina’s reserves weren’t stable even before electoral uncertainty spiked in September and October. If the new funds from the IMF and other official lenders (the World Bank and Inter-American Development Bank) are excluded, Argentina drew down its reserves by about $10 billion between the end of December and the end of August.

Exports aren’t likely to grow much more either, though the October total will be bolstered by the one-off sale of a bunch of stockpiled soybeans after the export tax was temporarily lifted.

Avoiding an even bigger current account deficit over time thus requires slowing the pace of import growth. And there isn’t yet evidence that the peso is now weak enough to discourage Argentines from shopping abroad. In fact, there is more than a bit of evidence to the contrary.

There are two additional factors that complicate Argentina’s path to regaining financial autonomy.

The monthly adjustment in Argentina’s exchange rate band is only a percentage point, and inflation is still rising at much higher monthly rate. That implies that the adjustment that happened to Argentina’s inflation adjusted exchange rate over the course of 2025 will be slowly reversed in 2026.

Santiago Resico put it well in Bloomberg: “With inflation running at 2%, and the bands at 1%, you’re going to continue appreciating the real exchange rate, which will create problem.”

Argentina also faces substantial external debt payments in January. IMF data shows $5 billion in principal and $3 billion in interest on the government’s external debt is due in the first half of 2026. Most of that is due in January, and there are slightly larger payments in the second half of 2026.

In other words, Argentina’s usable reserves will likely fall to critical levels early in 2026 without a substantial influx of new money from the United States. Treasury Secretary Bessent’s call for Argentina to now finance itself in the market is hope masquerading as a plan; any market financing will be expensive and put additional pressure on Argentina’s reserves over time.

The right choice here is pretty obvious. See Professor Eichengreen. Argentina shouldn’t spend its remaining reserves and $20 billion from the U.S. defending an exchange rate band that it likely cannot sustain. Better to let the peso adjust—whether by allowing a float or adjusting the band—and then seek to rebuild reserves from a stronger starting point.

Argentina, after all, really does need a plan that allows it to pay down $5 billion a year in principal on its external bonds and on its dollar-denominated central bank bonds (BOPREALs) while rebuilding its cash position and generating the funds to repay China, the U.S., and ultimately the IMF.

The total that Argentina may need to repay could easily approach $100 billion if the full $20 billion from the U.S. is used.** That’s a tall order, and one that is most easily achieved by a country that is running a current account surplus and that can use any market access to refinance official debt rather than finance ongoing deficits.

But right now, both the Argentine government and the U.S. Treasury Secretary seem inclined to defend the Argentina’s existing exchange rate arrangement.

That runs a big risk of proving over time to be mistake.

Foreign debt is not, in fact, paid out of fiscal adjustment. It is paid out of foreign exchange reserves. Argentina’s fiscal accounts improved under Milei. But its external accounts deteriorated. A balanced budget was consistent, thanks in part to a behind-the-scenes credit expansion and relatively loose monetary policy in 2024 with a growing external deficit.

But external deficits need to be financed. Private markets aren’t open at a realistic price. The IMF’s willingness to replenish Argentina’s reserves has been exhausted. It is now up to the Treasury to decide if it really is willing to do whatever it takes to allow Argentina to maintain its exchange rate band—and the associated external deficit.

* Cash export proceeds have been juiced in recent months by various special exchange rate rates and tax concessions. The improvement in the foreign exchange balance from trade in the third quarter in the BCRA’s monthly data on foreign exchange flows is thus unlikely to be sustained.

** Argentina has also used its $6 billion SDR allocation, which isn’t a risk per se as the SDR allocation won’t be called. It does however create an additional interest payment that the central bank has to pay as it has an SDR liability, but no offsetting assets. The fact that is has been used helps highlight how Argentina really used all possible sources of foreign exchange.

*** Wags already call the IMF the AMF (the Argentine Monetary Fund). The U.S. Exchange Stabilization Fund (ESF) could soon be the PSF (the peso stabilization fund) as well; all $22 billion of its liquid dollar holdings have either been used to buy pesos or committed to the Argentine swap facility. Additional support would require, well, using the ESF’s large holdings of SDRs, and that isn’t something that would obviously have a lot of Republican support.