This article was published in Vol. 4 No. 1 of our print edition.

Introduction

Dollarization, or in the case of some Eastern European countries euroization, is an economic occurrence when foreign currency is used in parallel with the domestic currency. There are various degrees of dollarization/euroization. The reasons for this phenomenon are country-specific, but in most cases, the root cause is the instability of the domestic currency.1

In the case of the US dollar there is also another level of dollarization, namely the global level. The US dollar is used as a global reserve currency and a global trade currency. Most economic trade and a significant amount of global debt are dollar-denominated. Very few countries in the world do not have any dollar debt, either in the form of a dollar debt issued or in the form of dollar-denominated holdings. According to Bertaut, Beschwitz, and Curcuru (2021),2 over 60 per cent of non-domestic debt issuances are in US dollars.

Thus, there are two global uses for the dollar: debt and asset holdings. Some countries, in order to gain global recognition or to attract global investors, issue debt denominated in dollars. Issuing dollar-denominated debt is the first step in getting noticed by global investors. If a country has a small economy and limited economic stability, issuing dollar-denominated debt will show the country wants to attract foreign investors and seeks economic stability. Issuing debt in a foreign currency creates a strong incentive for local currency stability.

Countries, banks, private individuals, and especially central banks will keep a portion of their assets in USD-denominated debt and US-issued debt. Again, the main reason is global liquidity, the stability of the issuer, and size. For the last hundred years the US has been the single largest global economy, possessing the largest stock market and the most powerful army. All these elements are the reason why a person or private, public, or government entity would want to hold USD-denominated assets. Given the size and global importance of the US, the dollar is also employed as the main currency for global trade.3

These are the financial facts of today’s globalized world. But this world order is being disrupted. In 2023 China and the other BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, and South Africa) have explicitly stated their desire to remove the dollar from its throne as the world’s leading currency. As Brazil’s President Lula recently put it: ‘Every night I ask myself why all countries have to base their trade on the dollar.’4

The desire to remove the dollar from its global throne might seem like a pipe dream, but the prospects of it occurring are not so far-fetched and are more concerning. This paper argues that the intention of the BRICS group is not to remove the dollar as the global store of value or to replace the dollar as the main currency for global transactions. Their goal is to slightly decrease the use of the dollar for transactional purposes. As this paper will demonstrate, even a small decrease in the use of the dollar as a global currency for transactions will have a significant impact on the Western financial world.

1. The Global Dollar Flow

The world as we know it today has evolved from the post-Bretton Woods system, founded on the free flows of goods and capital. In terms of globalization and the importance of the dollar, the rise and the fall of the Bretton Woods system are equally important.

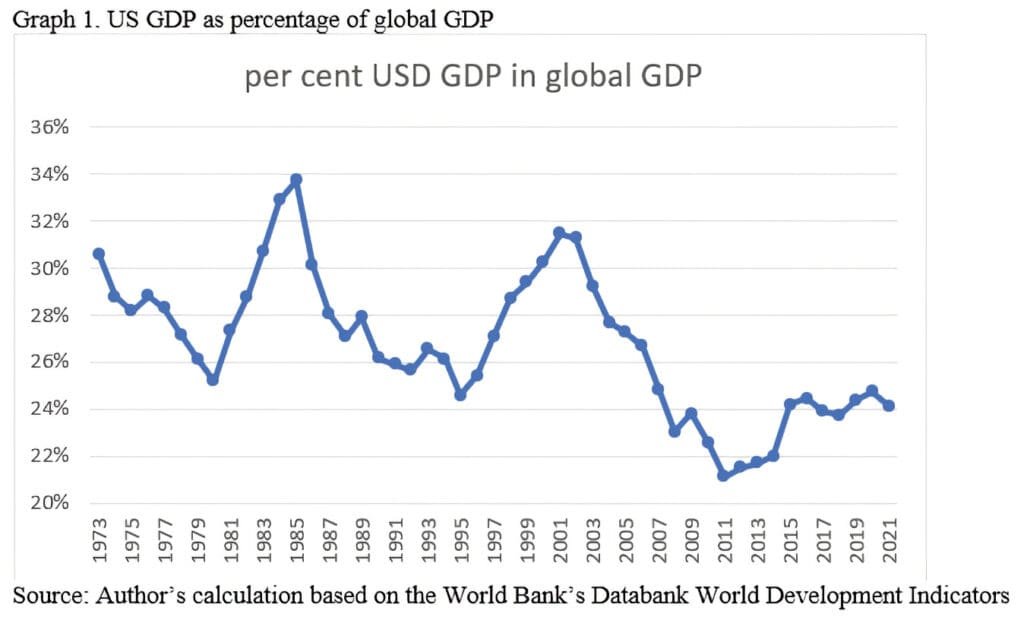

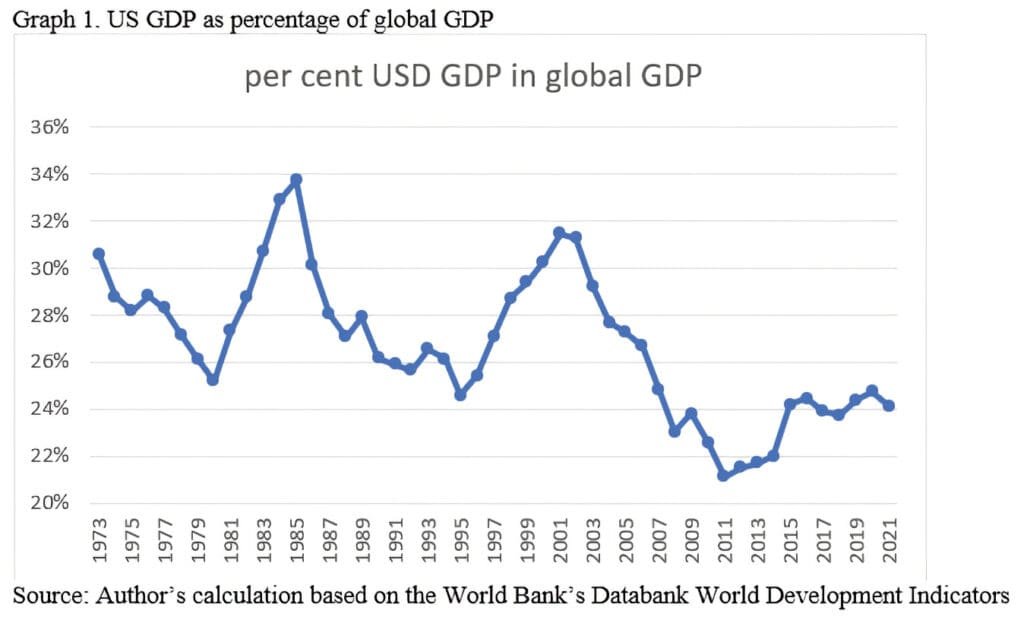

After 1945 the USA emerged as the leading global nation, having both military and economic supremacy. In this paper, we are going to focus on economics. As shown in Graph 1, since 1945 the US has held the largest share of the global economy. When the Bretton Woods system was abandoned, the US still accounted for over 30 per cent of global GDP.

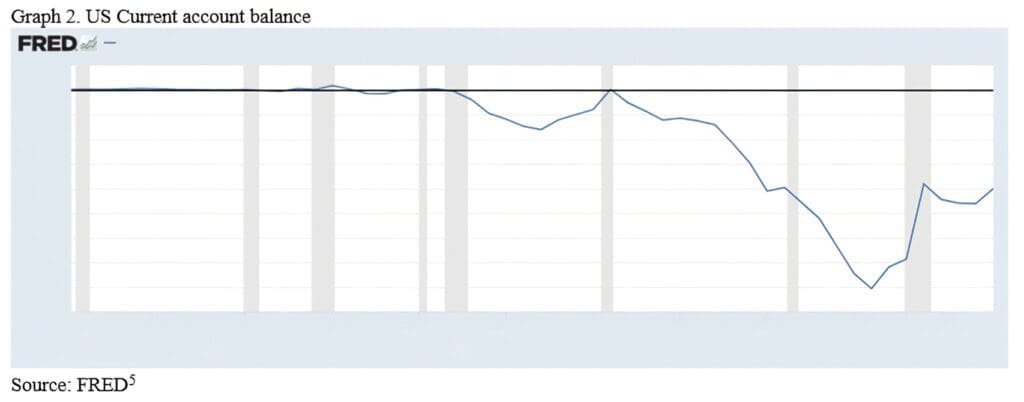

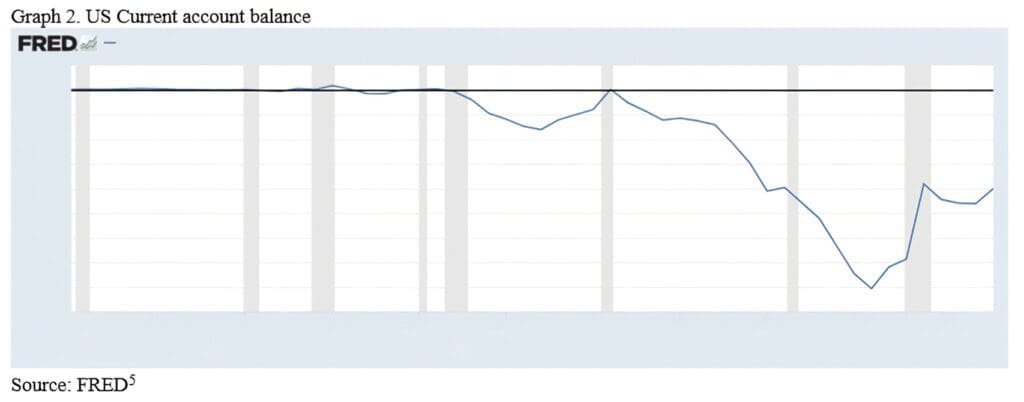

With the fall of the Bretton Woods system, capital controls were removed and the US started to build trade and budget deficits at the same time. This economic occurrence is known as the twin deficits.

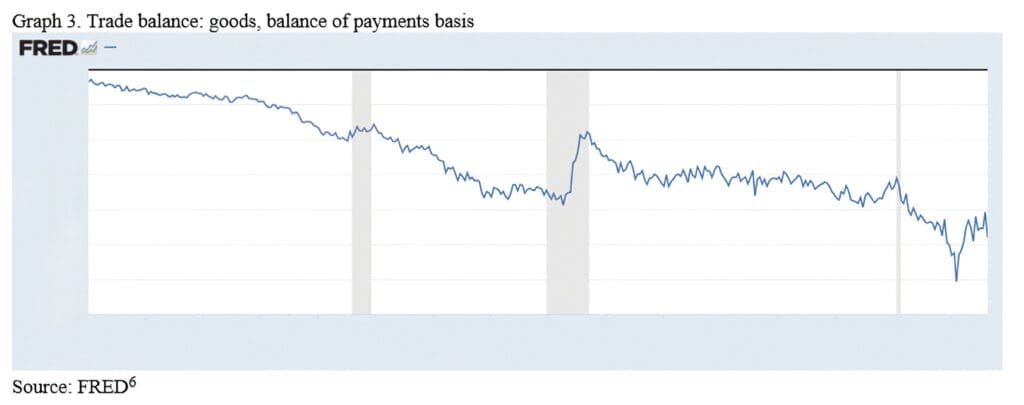

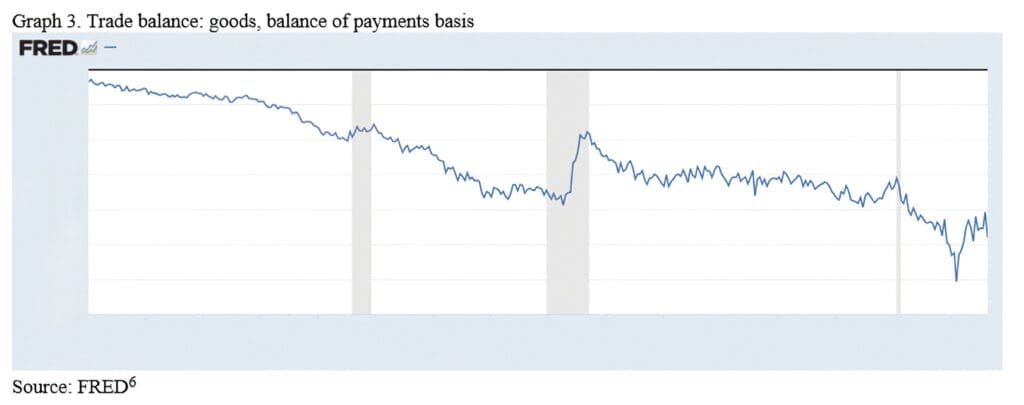

The data from 1973 shows the US economy oscillating around 30 per cent of global GDP. Taking the year 1973 as a starting point of reference, we are going to look at two more series. The first one is the balance on current account and the second is the trade balance. The reason why we are looking at the two series is the fact that the balance on the current account was discontinued by the FRED database.

Both of these series show that after the dissolution of the Bretton Woods system, the US started to experience a significant trade deficit. The large US trade deficits have significant global implications, especially for the Western world. Here is why: If we look at the global economy, trade deficits and surpluses must sum to zero. If country A has a trade deficit of 10, then country B must have a trade surplus of 10, otherwise, where would the goods come from?

The fact that the US has run significant deficits has major implications for the rest of the world. Let us examine the following calculation: in the year 2000, the US economy accounted for around 30 per cent of global GDP and its trade deficit was 446 billion USD. At the same time, global GDP was 33.8 trillion and US GDP was 10.3 trillion USD. This means that the rest of the world’s GDP was 23.5 trillion dollars. However, the US consumed 10.7 trillion USD (consumption is larger than GDP because of the trade deficit, since the US is consuming imported goods) and the rest of the world produced 23.5 trillion dollars, but without extra US consumption it would have produced 446 billion less (the rest of the world produced more and exported more to the US market). Because the US was running a trade deficit of circa 1.5 per cent of global GDP, the rest of the world was able to produce 1.8 per cent more. Higher production led to more jobs and higher economic growth for the rest of the world.

In essence, by being the largest economy in the world with a high trade deficit, the US was fuelling economic growth in the rest of the world. Let us consider a counterfactual. If the US had not had such a high deficit, the rest of the world would be much poorer and less economically developed. Deeper data analysis in this article is not possible because of space restrictions. But even this simple example clearly shows the impact and importance of the US trade deficit on the rest of the world’s economic growth.

As a byproduct of the trade deficit, the US sent out dollars into the world. In order to buy goods overseas, either the overseas country had to accept dollars or the US had to sell dollars and buy these other countries’ currencies. The arrangement of goods for dollars worked perfectly for both sides. Most countries needed dollars to transact with other countries, since global trade is dollar-denominated and they wanted to hold dollars as a store of wealth. If a country held too many dollars in cash, the country could always buy US debt (treasuries) as a store of value.

Thus, an ideal financial working relationship was formed. The US consumed more than it produced, leading to higher consumption for the average US consumer. The rest of the world produced more than it consumed, which led to a higher level of employment, production and GDP growth. The extra dollars were used for trade transactions and to purchase US debt. The funds returned to the US through debt allowed the US government to run budget deficits, and to spend more than it received from budget revenues.

‘If all BRICS states were to enter into an alliance, it would become a major alternative to the EU and G7’

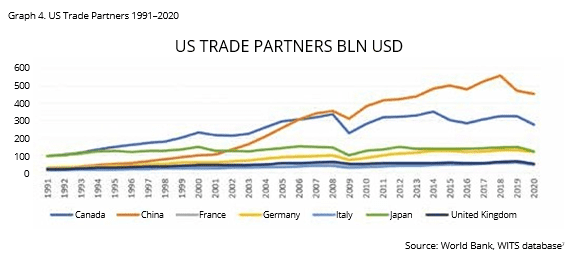

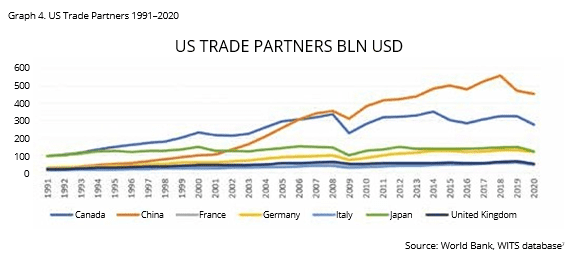

The process we have described pits the US against the world. Now we have to shift the analysis from the US versus the world to a more specific analysis of which counties benefited most from this arrangement. Referring simply to ‘the world’ puts every country on an equal footing in terms of benefits from US overconsumption. Clearly this was not the case. Most of the benefits from US overconsumption went to the primary trade partners of the US.

We are now going to compare imports from the G7 and China.8 As we can see from Graph 4, until 1990, Japan and Germany were major US trade partners. Therefore, US overconsumption contributed to the economic growth and wealth of these counties. By 2019, however, China held 37 per cent of the leading countries’ trade with the US. Therefore, the major beneficiary of US overconsumption has shifted over the last 30 years from the G7 countries to China.

2. The Emerging G2 World

In 2023, it became clear that the BRICS countries are not just a loose group of emerging countries but are in fact positioning themselves as a major global partnership9 with the principal aim of challenging the global status quo. If all BRICS states were to enter into an alliance, it would become a major alternative to the EU and G7.

In the previous section we have shown that China reaps major benefits from trade with the US. This is frequently mentioned as an argument to show that China will need to maintain a good relationship with the US simply because it cannot afford to lose such a valuable trade partner. This argument precludes the possibility that China may develop new partnerships with other countries, a possibility which we shall now investigate.

The US–China partnership was certainly important for China when the US represented 30 or 40 per cent of global GDP. But as Graph 1 shows, the US is rapidly losing importance in terms of its economic size. Also, by creating a large partnership with the BRICS economic group, China will be able to substitute trade with US with trade from other members of the BRICS group.

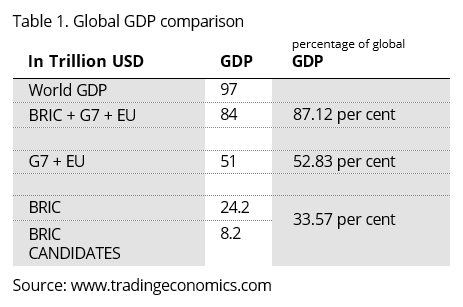

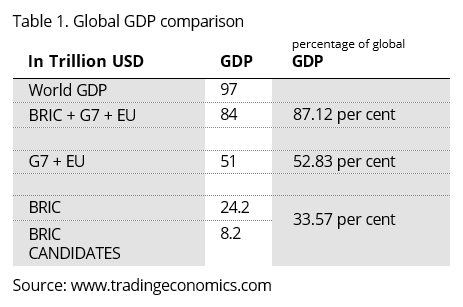

The list of new countries that have applied for or are expected to apply for BRICS membership is given in Table 1 below, together with their respective GDPs. The figures with the GDPs of the G7 and EU is also given. As we can see, any Chinese loss in G7 market share will be more than compensated for by the new countries,10 which together hold an increasingly significant position in the global economy.

There is another important element that needs to be mentioned here, and that is economic growth. We have shown that the US was a significant source of global economic growth, especially for the G7 and EU countries. US overconsumption fuelled exports from overseas markets. During the period following the Second World War, the most significant example of this was the Marshall Plan. What followed the plan was its substitution by a growing US current account deficit to support Western European growth. But as we have shown, over the last 30 years most growth benefits from the US deficit went to China, not to the EU.

The gradual decline of US economic size as a percentage of global GDP will also exert a major negative impact on economic growth in the rest of the G7/EU countries. A rise in public debt, interest rates, and the possibility of stagflation are all scenarios the G7 countries will now have to confront.

It is also important to analyze the growth trajectory of the G7 compared to the BRICS group and its potential new members. The G7 economies are old, highly capitalized, highly educated economies whose long-term potential for economic growth is around 2 per cent per annum.11 On the other hand, countries that want to join the BRICS group are mostly underdeveloped with high potential growth rates. Joining BRICS would offer the prospect of investment in infrastructure, education, and technology–all necessary elements for double-digit growth over the next several years. IMF projections have already predicted that most of the global growth in the future will come from the BRICS countries, and not from the G7, in spite of their relative size.12

Surprised? Intrigued? Worried? The scenario presented here reveals what China, and the BRICS countries are trying to achieve through a process of de-dollarization. It is not about the decrease in the use of the dollar on a global scale. It is about restructuring the global economy and the relative economic importance of particular global blocs.

3. The BRICS De-Dollarization

We now move to the subject of de-dollarization in terms of the actual transactional use of the dollar and what its short-term impact will be on both the US and G7 economies. We have shown the relationship between US trade and fiscal deficit and its impact on economic growth across the rest of the world. We have also shown that over the past 30 years China has reaped major benefits from the US trade deficit. We have further shown the possible path for future economic growth and the implications of expanding membership of an evolving BRICS union. We have also made the point that the dollar is used for two basic functions: as a store of value and as a transactional tool.

In recent months there has been an intense debate about whether the US dollar will or will not be replaced as the main global currency. In this section we will distinguish between the use of the dollar as the main reserve currency on the one hand and as the main currency used for transactions on the other. We will also investigate the possibility of a decrease in the use of the dollar for transactions and as a store of value.

The dollar is firmly established as the main global store of value.13 There are several reasons why this is the case and why it will remain so for at least a decade or more. First, the US is still the largest and strongest global economy. China is growing, but the US is still the global economic hegemon, possessing the most developed financial markets, and is the globe’s financial centre. The US also has the largest public debt in the world, which makes its public debt readily available to anyone who wants to possess it. In contrast, China and its renminbi possess none of these characteristics.

The dollar is recognizable and generally accepted for transactions and as a substitute currency around the world. It is the most convertible currency in the world. At the same time, the US is facing stagflation and rising public debt. But these are not reasons to not hold US debt. Business cycle oscillations, like recession and stagflation, increase the short-term demand for the dollar simply because the dollar is still a safe-haven currency.

There is also one other major factor explaining why the dollar cannot lose its global status quickly. Most holders of US debt are G7/EU countries which are not going to abandon the dollar, and which together represent a significant portion of the global economy. Therefore, the complete abandonment of the dollar seems highly improbable.

There is no obvious answer to the question of which currency could replace dollar-denominated debt as the main store of value. Currently, there is no currency that can replace the dollar as the main store of value. A similar argument can be made regarding the dollar as the main transactional currency. Since there is no way to replace the dollar as the main global store of value, there is no way to replace the dollar as the main global trading currency either.

So, the argument that the dollar will lose its status as a reserve currency is weak at best and far-fetched at worst. But replacing the dollar as the main transactional currency and the main store of value is not what BRICS countries, or China in particular, want. Everyone knows that the dollar cannot be replaced as a reserve currency, but its use for global transactions can be significantly decreased. This is what China and BRICS countries really hope to achieve.

In the second part of our paper we have shown how the dollar has been leaving the US over the last fifty years. The US government estimates that almost half of US dollars are held outside of the US.14 The BRICS countries have announced that they will create a parallel currency to the dollar, or will move towards increasing use of local currencies for transactions. In either of these two cases the use of the dollar will decrease, but will not stop.

In order to understand the implications of such a decrease in the use of the dollar we will now briefly review the transactional use of the dollar. Let us take a company that participates in international trade. If the trade is transacted in dollars, the company will have to hold some cash in dollars to be able to execute transactions. Occasionally the company will also buy or sell a portion of its dollar holdings depending on its transactions.

If this company subsequently includes another currency in its trade, its need for dollar holdings will decline and it will sell its dollars on the open market and exchange them for the new currency in which transactions are being conducted. This is an example based on one company, but if many companies over the world decide to decrease their dollar holdings, the global currency markets will have an increased supply of dollars and the dollar will decline in value.

The devaluation of the dollar should be perceived from three equally important standpoints. The first is the fact that once one currency devalues, its alternative appreciates. The devaluation of the dollar will mean the appreciation of the euro. Hence the terms of trade for the euro will worsen. The second

important point is the fact that devaluation of the dollar will increase inflationary pressures in the US, since important goods will become more expensive. The third point is that the dollars which have left the country will not return to the US. Currently the US Federal Reserve (Fed) is conducting a restrictive monetary policy. The Fed fund rate is targeted at between 5 per cent and 5.25 per cent, with the expectation of at least one more 0.25 per cent increase this year. The Fed is also conducting quantitative tightening to the amount of 95 billion USD per month (60 billion in treasuries and 34 billion in agency mortgage-backed securities).15

The flow of US dollars back to the US would increase the quantity of money in the US and consequently exacerbate inflationary pressures. The Fed will have to keep interest rates higher for longer and will have to continue shrinking its balance sheet for longer than anticipated a year ago. Sustaining the expected higher interest rates and quantitative tightening will have an important impact on the US economy. Higher interest rates will push the economy into recession and a decrease in the Fed’s balance sheet will increase the free floating of US market debt.

The combination of the rise in the US deficit and the Fed’s decision to shrink the balance sheet will saturate the global markets with US debt. This will push long-term US interest rates higher, causing an even larger economic slowdown. As a result of recession and the rise in debt and interest rates, the US will have to undergo fiscal consolidation. The fiscal consolidation will bring about an economic slowdown at a point in time when BRICS countries are becoming more and more united.

As we have shown here, de-dollarization might be a long-term goal of the BRICS group. But in reality it has very important short-term implications, including the weakening of economic growth in the G7 countries and increasing interest rates. The weakening of the G7 position on the global economic and political stage will become more and more evident.

Conclusion

We have pointed out that the complete abandonment of the USD as a global currency for trade, banking transactions, and as a store of value is not feasible in the immediate future. We have also shown that the removal of the US dollar as the main global currency and as a store of value is not an immediate goal of the BRICS group. In the short term, the process of de-dollarization is exploiting the current state of the business cycle in the US and EU. Just a small decrease in the number of transactions in which the dollar is denominated will cause a devaluation of the dollar and a prolonged state of higher interest rates in the US, together with quantitative tightening—all leading to a weakening of the economic position of the US, the EU, and the other G7 countries.

NOTES

1 For a review of the use of the dollar in global economy, see Daniel Fried, ‘The U.S. Dollar as an International Currency and Its Economic Effects: Working Paper 2023-04’, Working Papers 58764, Congressional Budget Office, 2023.

2 Carol Bertaut, Bastian von Beschwitz, and Stephanie Curcuru, ‘The International Role of the U.S. Dollar’, Federal Reserve (6 October 2021), www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/the-international-role-of-the-u-s-dollar-20211006.html.

3 For data on global invoicing in dollars, see Bertaut, Beschwitz, and Curcuru, ‘The International Role of the U.S. Dollar’.

4 Joe Leahy, ‘Brazil’s Lula Call for End to Dollar Trade Dominance’, Financial Times (13 April 2023), www.ft.com/content/669260a5-82a5-4e7a-9bbf-4f41c54a6143.

5 FRED, Economic Data, St. Louis FED, Balance on Current Account, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/BOPBCAA.

6 FRED, Economic Data, St. Louis FED, Trade Balance: Goods, Balance of Payments Basis, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/BOPGTB.

7 ‘World Integrated Trade Solution: United States Imports by Country and Region in US$ Thousand 1991–2020’, WITS World Bank Data Base, https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/USA/StartYear/LTST/EndYear/LTST/TradeFlow/Import/Indicator/MPRT-TRD-VL; and https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/USA/StartYear/1991/EndYear/2020/TradeFlow/Import/Partner/ALL/ Indicator/MPRT-TRD-V, accessed 2 September 2023.

8 See sources in note 7 above.

9 ‘19 Countries Express Interest in Joining BRICS Group’, The Times of India (25 April 2023), https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/world/rest-of-world/19-countries-express-interest-in-joining-brics-group/articleshow/99756285.cms?from=mdr.

10 ‘More than 30 Countries Want to Join the BRICS’, New Zimbabwe (24 May 2023), www.newzimbabwe.com/zimbabwe-expresses-interest-in-joining-brics/; and https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2023/05/24/more-than-30-countries-want-to-join-the-brics/.

11 For example, members of the FOMC project long run real growth for the US to be 1.8 per cent, www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20230614.pdf.

12 The IMF already predicts that most of global economic growth will come from BRIC countries. See www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2023/04/11/world-economic-outlook-april-2023.

13 ‘International Monetary Fund: Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves’, IMF.org (30 June 2023), https://data.imf.org/?sk=e6a5f467-c14b-4aa8-9f6d-5a09ec4e62a4.

14 ‘U.S. Currency in Circulation’, U.S. Currency Education Program, www.uscurrency.gov/life-cycle/data/circulation#:~:text=As per cent20much per cent20as per cent20one per cent2Dhalf,50.3 per cent20billion per cent20notes per cent20in per cent20volume.

15 ‘Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System: Press Release, 14 June 2023,’ Federal Reserve, www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/monetary20230614a1.htm.

Related articles: